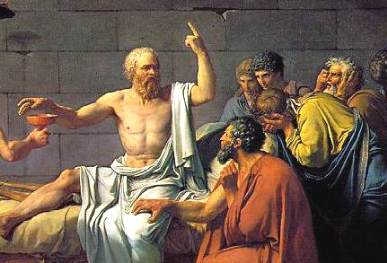

In our last post from the “tradition chapter” draft of my forthcoming Medieval Wisdom: An Exploration with C S Lewis, we saw that Lewis and the medievals shared a deep appreciation for the wisdom of the pagan philosophers. Was this some antiquarian hobby for Lewis, like collecting old stamps? Here we dig deeper: what possible use could the old philosophers still have for us today?

It is hard to overstate how much Lewis valued pagan knowledge. He had been told as a boy that “Christianity was 100% correct and every other religion, including the pagan myths of ancient Greece and Rome, was 100% wrong.” But because he had already encountered the wisdom of the philosophers, he found that this insistence on the opposition of Christianity to paganism drove him away from, rather than toward, the Christian faith. As it turned out, he abandoned his childhood faith “largely under the influence of classical education.”[1]

It was to this experience of valuing philosophy highly and then being told that Christianity must supplant it that Lewis owed his “firm conviction that the only possible basis for Christian apologetics is a proper respect for paganism.” This is a key connection with Boethius: a Christian who believes in the wisdom of classical philosophy and sets out to translate all of Aristotle for his day (Greek to Latin). Lewis, likewise, set himself a “translative” task in his age.

Lewis felt a knowledge of pagan classical authors was the essential prerequisite, and in fact much of the substance, of a knowledge of the Middle Ages. He said as much in a letter to his American friend Sister Madeleva, when she asked him for a strategy to familiarize herself with the field.[2] He once said, “If paganism could be shown to have something in common with Christianity, ‘so much the better for paganism,’ not ‘so much the worse for Christianity.” Classical wisdom had always been fair game for Christian teachers. Why cut ourselves off from it now? In this as in so many other ways, Lewis was more medieval than modern.

As he wrote to Griffiths: “[I]t is only since I have become a Christian that I have learned really to value the elements of truth in Paganism and Idealism. I wished to value them in the old days; now I really do. Don’t suppose that I ever thought myself that certain elements of pantheism were incompatible with Christianity or with Catholicism.”[3]

In a 1944 address to the Socratic Club at Oxford, he made the point more emphatically, in relation to a theme that fascinated him—Pagan foreshadowings of the life, death, and resurrection of Christ: “Theology, while saying that a special illumination has been vouchsafed to Christians and (earlier) to Jews, also says that there is some divine illumination vouchsafed to all men. The Divine light, we are told, ‘lighteneth every man.’ We should, therefore, expect to find in the imagination of great Pagan teachers and myth makers some glimpse of that theme which we believe to be the very plot of the whole cosmic story—the theme of incarnation, death, and rebirth.”[4]

Was this just some scholarly antiquarianism on the part of the Oxford don? On the contrary, Lewis rooted his argument about the importance of the Old Wisdom firmly in his sense of the dangers facing his own day. For Lewis, the modern darkness of his “Dark Age” came from its materialism, its utilitarianism, its subjectivism. All of these compounded themselves by cutting modern people off from the wisdom that had made it all the way from the ancients to the time of Jane Austen and Sir Walter Scott.

We have said that Lewis warned his Cambridge audience that it now lived in a new Dark Ages. What light, exactly, did he feel was being lost in his day? Not “just” tales and songs, myths and poems, but the very wisdom that, following Barfield, he felt was inextricably embodied in that lost literature. What wisdom? The Christian Gospel? Well, yes, that. But more deeply, the particular complex, perceptive, philosophically sophisticated and morally robust appropriation of the gospel to the Pagan mind that Boethius epitomized. After all, Lewis said, “Christians and Pagans had much more in common with each other than either has with a post-Christian. The gap between those who worship different gods is not so wide as that between those who worship and those who do not. . . .”

In response to those who argue that the modern world is lapsing into Paganism, Lewis responded, in essence, “If only we would!” For there is wisdom in Pagan culture that we need (a “consolation” of philosophy). But alas, in this new Dark Ages, “The post-Christian is cut off from the Christian past and therefore doubly from the Pagan past.”

In the face of this darkness, compounded by two cataclysmic world wars, even Oxford’s students were wondering, Why study philosophy? Lewis responded:

“Good philosophy must exist, if for no other reason, because bad philosophy needs to be answered.” And where is that good philosophy to be found? “Most of all . . . we need intimate knowledge of the past.” (28) In short, Lewis saw himself as the educator, the popularizer, the traditioner who could become the Boethius for this new Dark Age. Of course he recognized (as had his model Boethius) that there are limits to all merely human philosophy. But its power could be great nonetheless. In his essay “Christianity and Culture,” Lewis reflected: “[C]ulture is a storehouse of the best (sub-Christian) values. These values are in themselves of the soul, not the spirit. But God created the soul. Its values may be expected, therefore, to contain some reflection or antepast of the spiritual values. They will save no man. They resemble the regenerate life only as affection resembles charity, or honour resembles virtue, or the moon the sun. But though ‘like is not the same’, it is better than unlike. Imitation may pass into initiation].”[5]

“There is another way,” he wrote, “in which [culture, especially literature] may predispose to conversion. The difficulty of converting an uneducated man nowadays lies in his complacency. Popularized science, the conventions or ‘unconventions’ of his immediate circle, party programmes, etc., enclose him in a tiny windowless universe which he mistakes for the only possible universe. There are no distant horizons, no mysteries. He thinks everything has been settled.”

A tiny, windowless universe. I am reminded of Chesterton’s definition of insanity: “The clean, well-lit room of one idea.” Our modern room is well lit by the bare bulb of science. But of what lies beyond, we see nothing. Like the children in the Silver Chair, trapped underground with the witch, we cannot even reason from the light bulb to the sun of heaven. For that, we would need to open the windows of culture. Lewis continues:

“A cultured person, on the other hand, is almost compelled to be aware that reality is very odd and that the ultimate truth, whatever it may be, must have the characteristics of strangeness—must be something that would seem remote and fantastic to the uncultured. Thus some obstacles to faith have been removed already.”[6]

[1] Michael Ward, “The Good serves the Better and Both the Best: C S Lewis on Imagination and Reason in Apologetics,” in Imaginative Apologetics: Theology, Philosophy and the Catholic Tradition, ed. Andrew Davison, 66; citing letter to the Revd Henry Welbon, 18 September 1936 (unpublished; in the collection of the Marion Wade Center, Wheaton College, IL).

[2] Need footnote here, from Letters.

[3] Get citation (Letters?): 133 – 4.

[4] Lewis, “Is Theology Poetry?” addressed to the Socratic Club at Oxford, 6 Nov 1944. Weight of Glory, 83.

[5] Lewis, “Christianity and Literature,” 23.

[6] Lewis, “Christianity and Literature,” 23.

Related articles

- The Pagan element of Christian tradition: All truth is God’s truth (gratefultothedead.wordpress.com)

- In which C S Lewis meets the “bookish people” of the Middle Ages and shares their love of old books with new readers (gratefultothedead.wordpress.com)

- C S Lewis and his homeboy Boethius – part II (gratefultothedead.wordpress.com)

- C S Lewis and chronological snobbery: “Why – damn it – it’s medieval!” (gratefultothedead.wordpress.com)

- C S Lewis and his homeboy Boethius – two “public intellectual” peas in a pod (gratefultothedead.wordpress.com)

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians

Pingback: Heavens to Mergatroid – Planetary Themes in Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia | Welcome to Narnian Frodo

Pingback: The Birth of Venus | G. C. Jeffers

Pingback: The Mysterious Presence of Tom Bombadil - The Imaginative Conservative

Pingback: Clement, Philosophy and Paganism | A Pastor's Thoughts